Empty Rebellion: The Philosophical Shortcomings of Modern Indian Atheism, Part 1

A critique of the Intellectual Bankruptcy of Modern Indian Atheists

“Opposition to godliness is atheism in profession and idolatry in practice. Atheism is so senseless and odious to mankind that it never had many professors.” - Sir Isaac Newton

Recently, there has been a substantial and growing presence of the Indian atheist community online, particularly among those who are vocal in their criticism of Hinduism, India’s dominant religion. However, a significant number of these self-identified atheists (Vijayendra Mohanty, Pranav Radhakrishnan, Shekhar Bhattacharya, Logical Aayam) seem to lack a formal or even basic educational background in philosophy. This is concerning because, while it is not a requirement for all atheists to be philosophically trained, those who position atheism as an intellectual enterprise—especially when it involves critiquing religious ideologies—should at least have a foundational understanding of the subject. Unfortunately, this level of intellectual engagement seems to be largely absent in the current wave of modern Indian atheism.

From a broader perspective, it appears that the majority of these individuals are driven more by political motivations than by genuine philosophical convictions. A substantial number of modern Indian atheists, particularly those with a pronounced critique of Hinduism, seem to view atheism not as a philosophical stance but rather as a political tool. For instance, many who align themselves with Ambedkar’s political ideology (Science Journey) often identify as atheists, specifically when it comes to rejecting the religious practices and philosophical underpinnings of Vedic Hinduism. However, a puzzling aspect of this category of contemporary atheists is that many of these individuals, while vehemently rejecting Hinduism, seem to harbor strong, even doctrinal, beliefs in Buddhism. Additionally, there is a distinct group of individuals, particularly in the southern parts of India, who identify as atheists primarily due to political motivations rooted in their alignment with the ideas propagated by the prominent social reformer P. Ramaswamy (commonly known as Periyar).

This enables to establish a clear dichotomy within the Indian atheist community: (a) political atheism where individuals adopt atheism primarily due to political motivations, and (b) philosophical atheism where individuals embrace atheism based on philosophical convictions.

For the sake of clarity and to offer a deeper understanding of the intellectual foundations of atheism, it is valuable to first address category (b) — those who embrace atheism based on philosophical convictions. This group represents a more classical understanding of atheism, one that is rooted in reasoned inquiry, skepticism, and a critique of religious beliefs from a standpoint of logic and empirical evidence. Therefore, section 1 deals with defining atheism, formally. Section 2 talks about the doxastic attitudes and Section 3 addresses the criticisms and responses. It aims to address how modern Indian atheists in a popular discourse misconstrue atheism as “lack-theism” and advocate for some superfluous terminology like “agnostic-atheist” that find no mention in the literature and are redundant.

1. What is Atheism?

Majority of the professional philosophers in the analytic philosophy of religion have argued in preference of defining atheism as the denial of theism; for the explicit claim that there is no God (Le Poidevin, 1996; Schellenberg, 2019; Rowe, 2007; Oppy, 2018). The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy also gives the following definition:

“[Atheism is] the view that there are no gods. A widely used sense denotes merely not believing in god and is consistent with agnosticism [in the psychological sense]. A stricter sense denotes a belief that there is no god; this use has become standard.” (Pojman, 2015)

Elaborate arguments about why this definition is widely accepted in academic philosophy, and why philosophers ought to construe atheism as the belief in the non-existence of god than a mere suspension of belief in God's existence, are provided in this academic article (Draper, 2000); interested readers are strongly advised to peruse the cited article. Therefore, it is only reasonable for us to construe Atheism as the proposition that God does not exist, or more generally, that there are no gods, and theism with the proposition God exists, or more broadly, that there's at least one god. These definitions can also be symbolized formally, as is demonstrated below in following sub-section.

1.1 Formalizing Definitions

The above propositions (sentences that are capable of being true or false, i.e., capable of having a truth value) can be symbolized in First Order Logic (also called predicate logic or quantifier logic) as follows,

“There are no gods” can be symbolized as∀(x)¬G(x). This formally means that for all x, it is not the case that x is God. This is the symbolic representation of the proposition of Atheism, as defined above.

“There’s at least one god” can be symbolized as ∃(x)G(x). This formally means that there exists some x such that x is God. This is the symbolic representation of the proposition of Theism, as defined above.

The notation used here is the standard notation in symbolic logic. (Magnus et al., 2021). While it is not necessary to define the domain here, we can usually get away with defining the domain as “all things.” What is of particular interest in symbolizing the propositions is that it demonstrates, formally, that atheism and theism are contraries; exactly one of them can be true. If atheism is true then theism is false, and if theism is true then atheism is false. This helps us to build a formal structure for our propositions, which can then be analyzed. Once we have established the symbolization for our propositions, we are now in a position to study doxastic attitudes.

2. What are doxastic attitudes?

Propositional attitudes are mental states that involve a person’s relationship to a proposition, typically expressed in the form "X believes that P" or "X hopes that P," where "X" is the subject and "P" is a proposition or statement. In philosophy, propositional attitudes are important because they help explain how individuals understand, reason about, and interact with the world and with each other (Nelson, 2024). Doxastic attitudes are, thus, a specific subset of propositional attitudes that pertain to beliefs—that is, they reflect a person's mental stance toward the truth or falsity of a proposition (Schwitzgebel, 2024). For example, “Abdul believes that the earth is flat,” is a subject “Abdul” having the doxastic attitude of belief towards the proposition “earth is flat.” To analyze doxastic attitudes logically, particularly in relation to theism and atheism, we can employ epistemic logic, which provides a formal framework for reasoning about belief and knowledge.

2.1 Formalizing doxastic attitudes

Belief: s believes p is true.

Disbelief: s believes p is false.

Suspending judgment: s neither believes p is true nor s believes p is false.

The three positions outlined above exhaust the possible stances an agent, s, can take regarding a proposition, p. Notably, when s believes that p is false, this belief commits s to accepting the negation of p (i.e., not p). This conclusion arises from the principle that if a proposition is true, its negation must be false, and if the negation of some proposition is true then the proposition itself must be false. While certain non-classical logics (Shapiro, 2024; Priest, 2008) might challenge this assumption, such considerations fall outside the current scope of discussion. Thus, with this trichotomy in mind, we can symbolize the three doxastic attitudes pertaining to the propositions “God exists” and “God does not exist.” We shall go with the particular definitions for simplicity rather than going with definitions that deal with universal and existential quantifiers.

φ: God exists

¬φ: God does not exist

B(a,φ): This formally means, an agent a believes that God exists. In other words, an agent a believes that φ (“God exists”) is true. This is what it means to be a theist.

B(a,¬φ): This formally means, an agent a disbelieves that God exists. In other words, an agent a believes that φ (“God exists”) is false. Following on what was explained earlier, if one believes a proposition to be false then it commits them to the negation of that proposition. Thus, if an agent a believes φ (“God exists”) is false then it commits them to the negation of it, ¬φ, (“God does not exist”). This is what it means to be an atheist.

¬B(a,φ)∧¬B(a,¬φ): This formally means, an agent a neither believes that God exists nor does agent a believe that God does not exist. In other words, agent a neither believes φ (“God exists”) is true nor false. This is the attitude of suspending judgment and is consistent with agnosticism in the psychological sense.

It is important to note that agnosticism is also an epistemic thesis concerning knowledge about the proposition. However, we will defer a detailed discussion of this topic to a subsequent article. One might conceive of a fourth possibility, formally, as B(a,φ)∧B(a,¬φ) but that would be a contradiction since that means that an agent a believes both “God exists” and “God does not exist.” This, as is plainly evident, is an absurd position to maintain. Having expanded on the doxastic attitudes and the definitions of atheism and theism, we shall now proceed in addressing the nonsensical statements that the aforementioned modern Indian atheists make while espousing atheism. The reader is advised to peruse section 2 until there's clarity about doxastic attitudes.

3. Criticism & Responses

3.1 “Atheists simply lack belief in the existence of God(s)”

This hackneyed statement peddled by modern atheists in the popular discourse, where they claim that someone who simply lacks belief in the existence of God as opposed to believing that God does not exist is an atheist, is quite problematic.

First, the mere suspension of belief in the proposition "God exists" is insufficient for atheism. Since it is claimed that the person who lacks belief in the proposition “God exists" is an atheist, we can represent it symbolically using the key in section 2.1. The symbolization would look something like this ¬B(a,φ). Notice the difference that lacking belief in φ (God exists) is a different position than believing ¬φ (God does not exist). The former is ¬B(a,φ) while the latter is B(a,¬φ). Having understood this difference, let's proceed in formalizing the statement made by atheists that, “the person who lacks belief in the proposition God exists is an atheist.” In formal terms, this can be translated as:

A: Every person who lacks belief in the proposition “God exists,” is an atheist.

Children, individuals with advanced dementia, those with intellectual disabilities, all animals, and even my computer would all be classified as atheists merely due to the absence of belief in the proposition "God exists." This, of course, is clearly false. Furthermore, agnostics also lack belief in the proposition, so according to statement A, they would also be classified as atheists, which is demonstrably incorrect. To illustrate this, consider the statement: "Every animal is a dog." This is false because not all animals are dogs. Conversely, the statement "Every dog is an animal" is true, as being a dog is a sufficient condition for being an animal. Similarly, statement A is false, as simply lacking belief in God is not a sufficient condition for atheism. Instead, we should modify A as:

A’: Every atheist lacks belief in the proposition “God exists.”

Secondly, albeit A' is true, it is trivial since it does not provide any significant information about the attitude that the agent holds towards the negation of that proposition i.e., “God does not exist.” If the person claims to be an atheist and does not believe "God exists" and also does not believe "God does not exist," then their position is indistinguishable from the psychological state of agnosticism, which involves suspending judgment on the matter, as explained in section 2.1 above. In this case, the atheist's stance becomes virtually identical to that of an agnostic, as both are characterized by a withholding of belief, rather than a firm stance for or against the existence of God. Thus, the agent would be classified as an agnostic, regardless of their personal identification as an atheist.

Therefore, for the two reasons explained above, atheism cannot be considered as simply lacking belief in the existence of God(s) but believing in the non-existence of God(s).

3.2 “But Oxford Handbook of atheism defines it as lacking belief in the existence of God(s)...so, I'll go with that definition”

This is yet another statement espoused by some modern Indian atheists like Vijayendra Mohanty, who do not quite understand the difference between propositions and psychological states. It is true that the editors of the Oxford Handbook of Atheism (Bullivant & Ruse, 2013) support the definition of atheism as simply lacking belief in the existence of god(s), with Stephen Bullivant (2013) defending it for its scholarly utility. He argues that it serves as an umbrella term for various forms of atheism, with adjectives like "strong" and "weak" used to distinguish them.

However, this overlooks the issue that if atheism is defined as a psychological state, then propositions (such as "there is no God") can't be considered forms of atheism. As a result, his "umbrella" term excludes supposedly the strong or positive atheism. This critique is further explained in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy in the entry on Atheism & Agnosticism. Oppy, 2018 also argues against the “umbrella" definition and advocates for defining atheism as belief in the non-existence of God(s).

3.3 “Well, you see, technically… I'm an agnostic atheist,”

This position is commonly adopted by atheists in popular discourse when differentiating between knowing "God exists" and believing "God exists." While these terms may, prima facie, seem to offer a nuanced distinction, they often appear redundant or nonsensical upon closer inspection. For example, if atheism is defined as lacking belief in the proposition and agnosticism as being unsure, then the conjunction becomes unclear. What exactly is the person unsure of? Are they uncertain about lacking belief in God? On the other hand, if they construe atheism as per the academic definition, i.e., believing in the non-existence of god (see section 2.1) and agnosticism as suspending judgement, then that’s a contradiction! How can one believe a proposition while at the same time suspend belief in that proposition? Hence, the terminology “agnostic atheist,” upon closer examination, seems incoherent.

Moreover, I claim that every person who lacks belief in the proposition “god exists,” is agnostic in the epistemic sense. This arises from the way “knowledge” itself is understood in academic philosophy. In epistemology, for any proposition p and subject S, “knowledge” is formally defined as:

S knows that p if and only if p is true and S justifiably believes that p.

What this definition establishes is that for S to know a fact p, three conditions must be met. S must believe the proposition, as knowledge requires belief. Knowledge also requires truth, since false propositions cannot be known. Finally, S’s belief in p may be correct by mere luck, but this does not equate to knowledge. Therefore, knowledge requires justification. In short, knowledge can be defined as justified, true belief. This model is popularly called JTB (Justification, Truth, Belief).

The reader can read a detailed account of JTB on SEP (Steup et. al, 2024). It turns out, as Edmund Gettier showed, that there are cases of JTB that are not cases of knowledge. JTB, therefore, is not sufficient for knowledge (Gettier, 1963). Nevertheless, the case of atheism and theism is not one of the Gettier cases, and the Gettier problem itself has its share of criticism in academic circles (Zagzebski & Sosa, 1996; Williamson, 2002; Unger, 1975). Therefore, we shall proceed with defining knowledge as per JTB. In symbolic logic,

K(a,φ) ↔ (φ ∧ B(a,φ) ∧ J(φ))

where,

K(a,φ): a knows φ

φ: God exists (assumed to be true, as per JTB)

B(a,φ): a believes φ

J(φ): φ is justified

What this formally means is that an agent a knows φ if and only if φ is true, and a believes φ, and a is justified in believing φ. So, for any agent to know some proposition, all three conditions must hold: truth of the proposition, belief in the proposition, and justification for belief. If any of these three conditions is not met, then it implies that the agent does not know the proposition. Thus, if a person lacks belief in some proposition, then they don't know the proposition even if the other two conditions hold. In context of the current discussion, if the atheist states that they lack belief in the proposition “God exists,” the second condition is not met. Therefore, it follows that they don't know the proposition i.e., they're already agnostic towards the truth value of the proposition by virtue of lacking belief in it; adding another agnostic before it makes it redundant! The proof is as follows:

K(a,φ) ↔ (φ ∧ B(a,φ) ∧ J(φ)) [premise]

¬B(a,φ) [premise]

¬K(a,φ) [MT, 2,1]

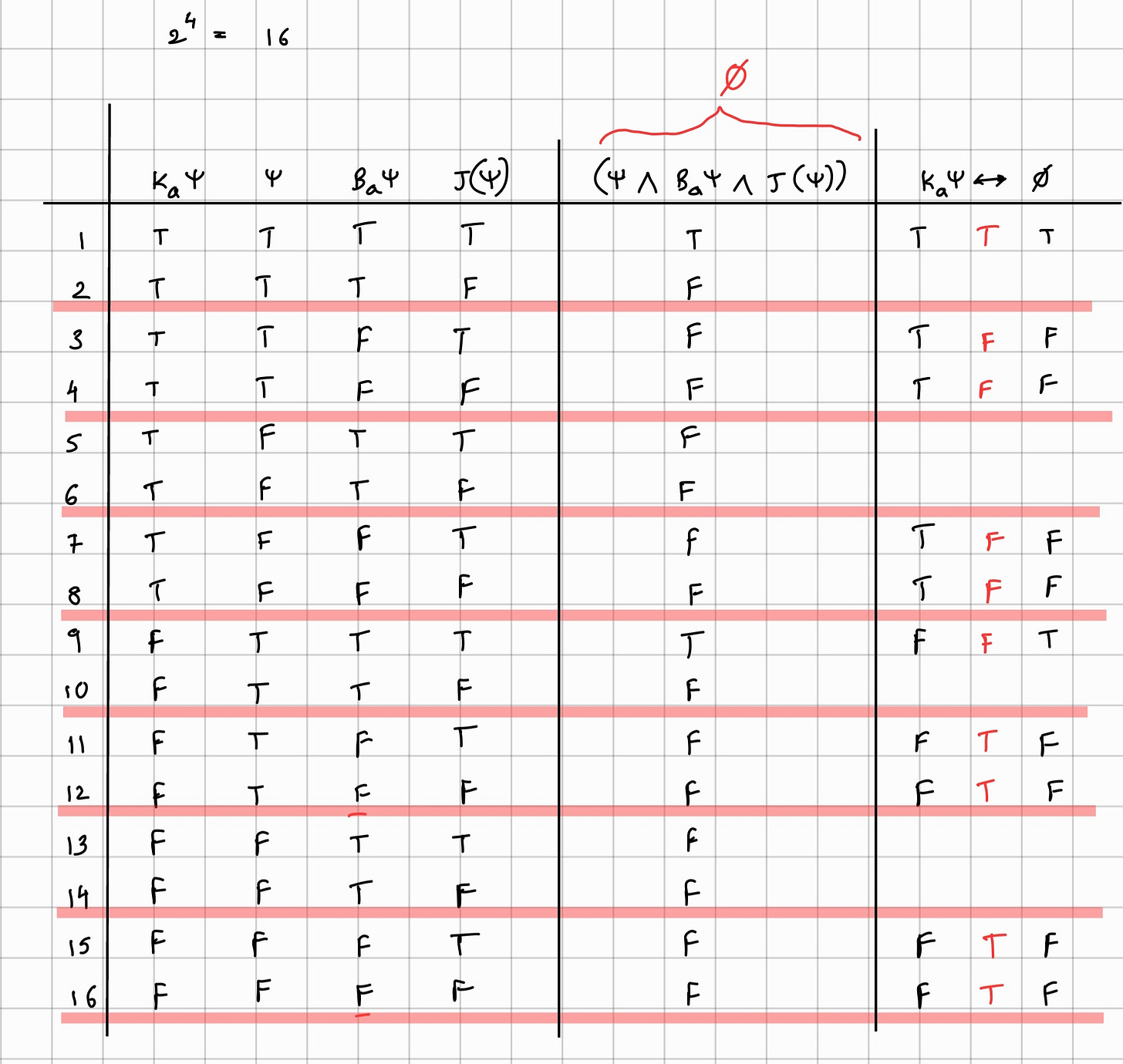

Let's see this with the help of the truth table formulation below:

As we can clearly see from the truth table above, all sixteen possibilities for the biconditional are given. In rows 1, 11, 12, 15 and 16 we see that the biconditional is true and those are the cases that interest us. Out of these rows, in 11, 12, 15 and 16, the condition for belief is false, therefore, the conjunction is false. From this, it follows that K(a,φ) is false as well i.e., when the belief is absent, there's no knowledge. Row 1 shows that when the conjunction is true, and the biconditional is true, K(a,φ), is true i.e., when belief, truth, and justification are true then there’s knowledge about the proposition. Hence, it is proved that everyone who lacks belief in the proposition, “God exists” is already an agnostic; adding another agnostic to it makes it redundant.

Additionally, such superfluous terminology is endorsed by figures like Dawkins and Harris in their books, which helps to spread these misinterpretations further. Nevertheless, from all the above reasons, it can be safely concluded that the term “agnostic atheist" is incoherent and redundant.

3.4 “All this is simply academic, people don't speak that way colloquially”

This approach is irrelevant; how a proposition is perceived colloquially has no bearing on whether it is true or false. It seems to be an attempt by some modern Indian atheists to avoid logical scrutiny of their views. By stating, “I just mean this in a colloquial sense," they aim to preempt further inquiry, allowing them to avoid defending their claims. Meanwhile, they continue to dismiss other positions without offering sound objections, and when they do present objections, they often lack substance.

Secondly, these modern Indian atheists frequently employ informal fallacies against their opponents in livestreams—fallacies that aren't typically found in everyday conversations either. After all, when was the last time you heard someone say, “That's argumentum ad lapidem!” in a casual debate? If they're willing to use informal logic, why shy away from formal logic? Perhaps it's because they lack literacy in formal logic, and engaging in such discussions would undermine their ostentatious rhetoric.

Conclusion

The article included a detailed exposition of philosophical atheism and we conclude that atheism should be defined as the denial of theism—the explicit claim that there is no God(s)—as opposed to merely suspending belief in the existence of God(s). We also deduce that the term "agnostic atheist" is incoherent and redundant in an epistemic sense. Finally, from the detailed discussions in the preceding sections, it is evident that modern Indian atheists need to educate themselves philosophically to present a more coherent stance and engage in genuine philosophical dialogue, rather than resorting to tantrums and maintaining incoherent positions. As Kant famously said,

"It was the duty of philosophy to destroy the illusions which had their origin in misconceptions, whatever darling hopes and valued expectations may be ruined by its explanations."

In the next article, we shall discuss the part (a) political atheism, and explore its problems.

Loved it bhargav bhai...But there was nothing new in this article for me as we have already discussed this for hours in my podcast as well as on WhatsApp Call.

I just hope these rented atheist will understand your point and correct themselves.But most of them are politically motivated atheist,they just want to s*it on religion specially Hinduism...They have no interest in these philosophical discussions.

Frankly speaking,

I was able to understand those weird symbols and truth tables just because of that formal logic book you sent me few months ago.

Thanks for mentoring and guiding me and yeah keep writing these articles...Intezaar rahega next article ka

[1]

<<Children, individuals with advanced dementia, those with intellectual disabilities, all animals, and even my computer would all be classified as atheists merely due to the absence of belief in the proposition "God exists." This, of course, is clearly false.>>

^Will this statement not be partially incorrect, given "your computer" has to be shown as identical to "a person", and so do "all animals", i.e., the Viśeṣa-lakṣaṇa or observable attributes that distinctly identify an entity of the category corresponding to a "human", and differentiate from other categories which aren't "human", should be unambiguously demonstrated in the case of the "computer" or "other animals". Given, the proposition before that is given as cited (𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘳𝘦𝘭𝘦𝘷𝘢𝘯𝘵 𝘱𝘰𝘪𝘯𝘵 𝘣𝘦𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘪𝘯 𝘊𝘢𝘱𝘴): <<A: EVERY PERSON who lacks belief in the proposition “God exists,” is an atheist.>>

[2] The criticism of "agnostic atheism" using JTB was well explained. But would it was needed to go forward with JTB as identical to knowledge, when that is already challenged by Gettier's problems (𝘎𝘦𝘵𝘵𝘪𝘦𝘳 𝘩𝘢𝘴 𝘤𝘳𝘪𝘵𝘪𝘤𝘪𝘴𝘮𝘴, 𝘉𝘜𝘛 𝘴𝘰 𝘥𝘰𝘦𝘴 𝘑𝘛𝘉)? Moreover, as first things first, does it not have to be accurately explained as to what "knowledge" is being talked about, given how does one "know" of belief, IF subjective reality and subjective truths are not identified as existing, besides objective reality and objective truths? Because then the question could be "what is belief?" or "why do we know of belief as belief?". How is one supposed to "know and explain" belief, given belief is made different from knowledge by treating belief to be an independent factor upon which knowledge is 'causally' dependent [𝓚(𝓪,φ) ↔ (φ ∧ 𝓑(𝓪,φ) ∧ 𝓙(φ))]? <= That's an infinite regress.

Also here: <<What this formally means is that an agent a knows φ if and only if φ is true, and a believes φ, and a is justified in believing φ. So, for any agent to know some proposition, all three conditions must hold: truth of the proposition, belief in the proposition, and justification for belief. >>

^The question would further be: Does believing a thing and knowing the thing, exist in the same space-time causal framework (𝘧𝘰𝘳 𝘪𝘯𝘴𝘵𝘢𝘯𝘤𝘦, 𝘪𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘴𝘢𝘮𝘦 𝘱𝘦𝘳𝘴𝘰𝘯 𝘢𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘴𝘢𝘮𝘦 𝘵𝘪𝘮𝘦 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘣𝘦𝘤𝘢𝘶𝘴𝘦 𝘰𝘧 𝘴𝘢𝘮𝘦 𝘤𝘢𝘶𝘴𝘢𝘭 𝘧𝘢𝘤𝘵𝘰𝘳𝘴); unless "belief is identical to knowledge" is demonstrable (𝘱𝘳𝘪𝘯𝘤𝘪𝘱𝘭𝘦 𝘰𝘧 𝘪𝘥𝘦𝘯𝘵𝘪𝘵𝘺)? I mean, why does one have to make a "choice" or "judgment" (𝘣𝘦 𝘪𝘵 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘰𝘳 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩𝘰𝘶𝘵 𝘫𝘶𝘴𝘵𝘪𝘧𝘪𝘤𝘢𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯) to accept something as true (𝘵𝘳𝘶𝘦 𝘣𝘦𝘭𝘪𝘦𝘧), and that too without (𝘰𝘳 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘪𝘯𝘴𝘶𝘧𝘧𝘪𝘤𝘪𝘦𝘯𝘵) empirical awareness or Pratyakṣapramāṇa of the thing believed to be true, IF the person is already knowing the thing to be true based on empirical awareness (𝘪.𝘦., 𝘢 𝘵𝘳𝘶𝘦 𝘧𝘢𝘤𝘵)? Also, with such multiple assumptions without clear explanations as to the distinctions (𝘴𝘶𝘤𝘩 𝘢𝘴 𝘣𝘦𝘵𝘸𝘦𝘦𝘯 𝘣𝘦𝘭𝘪𝘦𝘧 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘬𝘯𝘰𝘸𝘭𝘦𝘥𝘨𝘦), does it not result in a "logically explosive" proposition (𝘱𝘳𝘪𝘯𝘤𝘪𝘱𝘭𝘦 𝘰𝘧 𝘦𝘹𝘱𝘭𝘰𝘴𝘪𝘰𝘯) and the absence of principle of parsimony (𝘖𝘤𝘤𝘢𝘮'𝘴 𝘙𝘢𝘻𝘰𝘳)?

-

Atleast in the context of Advaita Vedanta, the epistemological classifiers for metaphysical ontology (𝘉𝘳𝘢𝘩𝘮𝘢𝘯 𝘰𝘳 𝘚𝘢𝘵) is accepted, and thus the subjective/iti/Prātibhāsika, objective/iti/Vyavahārika, and transcendental or absolute or the non-dual/neti neti/Pāramārthika are accepted. Also, if certain Analytical philosophers and certain Empiricists are considered, who argue in the favour objective reality as knowable besides the subjective.